For today’s post, I wanted to translate an article I came across which I found interesting. It’s from the news website El País. I decided to try using the CAT (computer-assisted translation) tool I mentioned in yesterday’s post, but I gave up after a couple lines. The translations it produced were very clunky and I’m sure I’d end up spending more time cleaning up the translation than I would just translating from scratch!

Anyway, here we go! Here’s the original article in Spanish: http://cultura.elpais.com/cultura/2017/01/17/actualidad/1484673807_325607.html

The Difficult Translation of Humor

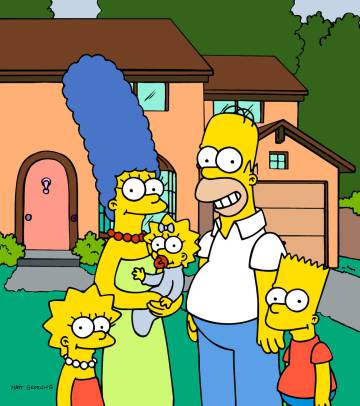

Getting Homer Simpson to be just as funny in Spanish or maintaining the plays on words in a series like “Modern Family” is a challenge for translators

By Patricia Pieró

Jan. 18, 2017 08:34 EST

When Bart Simpson wants a “Fresisuis” (Squishee), he goes to the “Badulaque” (Kwik-E-Mart) and if someone bothers him he tells them to “multiply by zero,” (“eat my shorts!”). These terms have formed part of the Spanish pop culture for almost three decades, the time the yellow family from Springfield has been on the air. Together with other expressions, like “mosquis” (“d’oh!”), these words came from the minds of their translators, not from the original creators. Making sure The Simpsons doesn’t lose its humor in Spanish, maintaining the plays on words of series like Modern Family or creating an entire linguistic universe in Adventure Time is a difficult challenge for translators.

“The essential thing is to try to maintain the funniness, even if the content is different,” notes María José Aguirre de Cárcer, translator of series like The Simpsons, Futurama, Seinfeld or Lost. Together with the late Carlos Revilla, who for many years was also the voice of Homer, she’s created a way of understanding life through the world of this long-running series. “Everything comes from the imagination and turns over and over in my head. The Simpsons is also an adventure because each chapter is very random; suddenly they start the episode in New York and they end up traveling to Mars,” she points out.

Tradition, politics, and — up till now — Spaniards’ lack of ease in English have fostered a strong culture of dubbing. In Europe, Spain — along with Italy — is the country which most often dubs audiovisual content, according to the findings of a 2011 committee of experts for the Ministry of the Economy with the goal of encouraging the use of original versions. The arrival of new television platforms like HBO or Netflix, or for the last seven years now, TDT, has opened a new range of possibilities to viewers when choosing the language in which they watch broadcasts, thus increasing their practice of and familiarity with a foreign language.

If achieving a good dub is complicated, humorous content, full of stereotypes, inside jokes and references to characters in a particular context make the issue even more complex. One clear example is the animated series — not necessarily for children — Adventure Time. Luis Alis is the man in charge of making its characters speak Spanish: “You always find a way to frame the dialogs in a way that cause the same hilarity in your language.” Alis believes that the success of this series is based on the double entendres in its content, but in exactly that point lies the difficulty of transferring all the meanings of a simple phrase to another language. “I remember one scene in which the character said, ‘Get your hot buns over here,’ which literally means ‘warm bread rolls,’ but in a figurative sense means ‘attractive butt.’ I had to translate it as, ‘Get your hot self over here.’ There’s always a solution,” he jokes.

On occasion, the tricks come through the body language or the manner of speaking of the characters themselves. The original “black English” of Waldo, Steve Urkel’s friend in Family Matters, was translated into the Spanish version as a Cuban accent. Meanwhile, the characteristic expressions of the characters in the comedies Welcome to the Sticks and Welcome to the South, based on stereotypes of France and Italy respectively, were resolved through characteristic ways of speaking for different characters. “Sometimes, the humor isn’t reached by what is said, but rather by how it’s said. In the Spanish voiceover, they don’t often draw upon special types of voice or unusual ways of speaking, but humor is precisely one of the cases in which they are used,” remarks Pompeu Fabra University professor Patrick Zabalbeascoa in the book Translation for Dubbing and Subtitling (Cátedra).

“Humor has a very strong cultural background,” claims University of Oviedo literature professor Marta Mateo. Globalization and social networks, nevertheless, have contributed notably to the dissipation of borders, even cultural ones. “When I was a teenager nobody repeated jokes in English, but nowadays all the youth know what the initials WTF mean (in Spanish: ‘Pero qué leches…’ — ‘What are you doing?’). Now there’s a transfer of terms through memes, for example, which are creating a shared slang,” notes Alis. “Perhaps American series travel abroad more easily because of the dominance of this culture in the world and because when they’re creating, they’re thinking more about the characterization of the characters,” Mateo specifies.

A Shared Culture

Globalization is one of the factors that has favored the disappearance of Spain’s typical humorous references that grated in dubbed versions. In one of the episodes of the fifth season of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Will Smith’s character makes a reference to Spanish rock singer Ramoncín, something which would seem pretty strange nowadays. Adapting a translation to the context of the final viewer is given the technical name “domestication.” “In general it’s not something I like much; if used poorly, it takes the viewer out of the movie or series,” explains Aguirre de Cárcer. The translator also stresses the importance of research and documentation in order to not goof it up. “One of the most complicated jobs I’ve had lately is Vynil (a series about the birth of hip-hop, punk and disco music in the ’70s). I’ve read novels from that era to master the slang they used.” Alis also remarks on the importance of mutual understanding that is created between the translator and the viewer: “After several chapters, a language is created and references shared and this allows you more freedom in the work. You don’t have to explain everything constantly.”

One unresolved matter is the viewing of content in its original language, something which is compatible with continuing to watch some dubbed content. 59.8% of Spaniards recognize that they don’t speak, write, nor read English, according to the latest measurements by the Center for Sociological Research. Nevertheless, this same study highlights that 94.8% of the population considers it important or very important to know a foreign language. One of the latest studies published on Spaniards’ English level, performed annually by Education First, places Spain 25th out of 72 countries. Language goes far beyond dictionaries, most of all when it comes to humor. Professor Marta Mateo affirms: “What one has to take into account is that the translated text will never be the same as the original. It’s another substance woven from other materials.”

***Lee here again!*** Whew! That was pretty good for one evening, I think! I did notice there were a few punctuation typos in the original Spanish article as well, and of course in order to do the translation I had to change some punctuation and a bit of sentence structure here and there to make it flow more naturally in English. I do, however, try to retain the style of the original as much as possible. I also had to look up all the names of the shows to make sure I got them down completely accurately, because I’m meticulous like that.

I made some editorial choices, such as including some of the Spanish words and phrases from the original article. I’ve watched some Simpsons episodes in Spanish, mostly when I was studying in Mexico, but I haven’t been an ardent fan in a long time so I wasn’t familiar with the words like “Fresisuis,” nor was I aware that in the Spanish version, Bart tells people to multiply by zero! If I were doing work for a client, I’d consult with them about whether to include such tidbits, but this was my translation for me so I did it how I wanted to!

That’s one of the things I love about translation. I love helping people understand each other, and at the same time, I get to learn new things! I hope you enjoyed reading the article and I hope it was interesting to explore Spaniards’ perspectives on foreign media.

1 Comment

Domestication vs. Foreignization vs. Localization | Lee the Linguist · July 20, 2017 at 8:03 pm

[…] Yesterday’s post brought up a point that I wanted to explore further. The article I translated from Spanish mentioned that in years past, dialog translators would often lean too far in the direction of “domestication.” An example they gave was that in the sitcom The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Will Smith’s character makes a reference to a Spanish celebrity named Ramoncín. Of course, Will Smith’s character in the show is an urban youth from Philadelphia and he would likely have never heard of Ramoncín, but the change was made to make the reference more comfortable for Spanish viewers. That’s domestication, making content more easily understood by the consumer by changing the content to what’s familiar. […]

Comments are closed.